What is the law on iBlastoids?

This week Professor Jose Polo and an international team have reprogrammed human adult cells to create an “iBlastoid” at Monash University. This breakthrough has opened a legal and ethical can of worms. Are the current laws ambiguous or superannuated?

The importance of these iBlastoids is that they enable us to learn how early-stage human embryos develop and implant in the uterus. It is claimed that they could lead to medical treatments for various problems such as infertility, miscarriage, developmental disorders and genetic diseases. They could provide insights into what happens during the black box of early human development between the 14th and 28th day after fertilisation. They could help women who have difficulties conceiving, have experienced miscarriages or are worried their child may have a genetic illness.

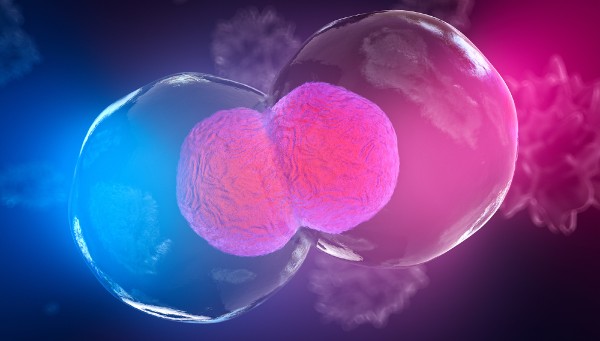

Usually an embryo begins with fertilisation of an egg by a sperm. After a few days, it is a tiny ball of around 100 cells called the blastocyst.

iBlastoids are formed by a different technique. Skin cells taken from the adult are reprogrammed using a method, developed by Nobel Prize laureate Shinya Yamanaka. These cells are directed to specialise into different types of specific kinds of cells. Given its blastocyst-like organisation, this structure is called iBlastoid,

Global guidelines and the legislation on embryo and stem cell research vary. Many Western societies have adopted a 14-day limit on research involving human embryos. Muslim countries also adopt this 14-day limit despite the religion’s much more liberal interpretations of the concept of ensoulment. In Australia, under the Prohibition of Human Cloning for Reproduction and the Regulation of Human Embryo Research Amendment Act 2006, it is illegal for scientists to allow the development of a human embryo outside the body of a woman for more than 14 days.

Is the 14-day limit antiquated?

An increasing number of bioethicists and scientists say Yes. Formulated by the Warnock committee in the UK in 1984, it was an arbitrary compromise between placating ambitious scientists and alleviating public concern when IVF was just beginning. The Australian researchers’ article in Nature said: “the developmental potential of iBlastoids as a model for primitive streak formation and gastrulation remains to be determined, and will require an international conversation on the applicability of the 14-day rule to iBlastoids”.

Recently, an international team of scientists and ethicists called for the 14 day limit to be scrapped. They recommended a “cautious, stepwise approach” to scientific research before extending the 14-day limit. This approach comprises various principles, including scientific justification, well-defined increments, independent peer review, public dialogue, informed consent and separation of clinical care and research.

It is not certain whether iBlastoids are to be governed by the same regulations. If they are treated as human embryos, they need to be destroyed by scientists on the 14th day. But the scientists contend that that iBlastoids are not really human embryos, just unfertilised cellular lab models of human embryos which could not result in live-born babies.

Others are sceptical about this. The Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, Anthony Fisher, is a bioethicist with a PhD from Oxford. He wrote in The Australian recently: “As the saying goes: ‘If it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, and swims like a duck, it’s probably a duck.’ So, too, with an embryo: if it has human genes, develops as a human being develops, and does the things a human embryo does, it’s probably an embryonic human being.”

The International Society for Stem Cell Research plans to revise the 2016 version of its guidelines for stem cell research and clinical translation. As embryo research laws worldwide differ, the ISSCR is regarded as a sort of de facto regulator. Though not legally enforceable, its guidelines will be very persuasive for legislators. They will be adopted by researchers, clinicians, universities, organisations and funding companies around the world.

The 2021 version of the ISSCR guidelines will released in May or June. It will be interesting what they will recommend on the issue of iBlastoids.

Dr Patrick Foong is a law lecturer at Western Sydney University. His research interest lies in bioethics and health law.

- Australia’s first human challenge trials centre opens - April 4, 2024

- FDA approves first gene-editing therapy - February 15, 2024

- Consumers should beware of stem cell treatments for Covid-19 - January 4, 2024