There is a bright side. If you catch Covid-19, you’ve missed out on bubonic plague

For a real epidemic, read ‘The Betrothed’

Milan is in the grip of an epidemic. Towns have been quarantined. Public gatherings have been cancelled. The streets are empty. Public officials try to dampen mounting hysteria. Dark rumours are circulating. Hospital wards are overflowing.

The coronavirus?

No, the Great Plague of 1630 in which perhaps a million (1,000,000) people died. About 35,000 have died so far in Italy’s coronavirus outbreak. That figure alone should immunise you against nostalgia for the Good Old Days. The panic and suffering of the citizens of Milan during the bubonic plague — who also had to cope with a drought, a famine and the Thirty Years’ War — make coronavirus seem like a Sunday summer picnic.

Europe, to say nothing of the rest of the world, has had plagues a-plenty, but Milan’s torment may be the best known thanks to its vivid description in the Great Italian Novel, I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed). Written by Alessandro Manzoni, it was published in 1827 and, apart from being used ever since to torment Italian high school students, it has become a benchmark for subsequent Italian fiction.

Like most 19th Century novels, it is a long, complicated narrative with dozens of vivid characters and abundant authorial commentary. It’s also a delightfully ironic love story with a deeply Christian outlook on life.

The plot runs like this: a simple peasant couple, Renzo and Lucia, are betrothed, but events tear them apart. Four hundred pages later, they are reunited in plague-stricken Milan and marry.

I’ve left a bit out: the cowardly parish priest, the villainous Don Rodrigo, the repentant l’Innominato, the perverse Nun of Monza, the saintly Fra Cristofero, the treacherous Griso, the corrupt lawyer Azzeccagarbugli, the erudite idiot Don Ferrante, etc.

But our focus is the Plague.

Manzoni based his vivid picture of the epidemic on extensive reading of contemporary accounts in Italian and Latin. If you want to be thankful for dodging a bullet by being born 400 years later than the events he described, dive into Chapters 31, 32 and 33.

There are instructive parallels with current events.

An angry populace. In China, Italy and elsewhere, people wonder if public authorities are telling the truth. Something similar happened in 17th Century Milan. The authorities initially denied that corpses left in the wake of invading German mercenaries were victims of the plague. Then they called it a mere “malignant and pestilential fever”. But soon it became impossible to deny: people were dropping dead in the streets with tell-tale black pustules in their armpits.

Panic. In the 21st Century, coronavirus panic is measured by rage on Twitter and panic buying in supermarkets. In the 17th Century, when the transmission mechanism of the disease was unknown, people blamed enemy agents from France. It was said that they went from house to house anointing door with the plague. Strangers were torn limb from limb in the streets.

Overflowing hospitals. In recent weeks there have been reports of hospitals in China turning away victims of the coronavirus because there are no beds. Naturally, Milan was much worse. Hospitals as we know them did not exist. There was only the lazzaretto, a vast shelter used in previous epidemics. The number of patients soon rose to 16,000.

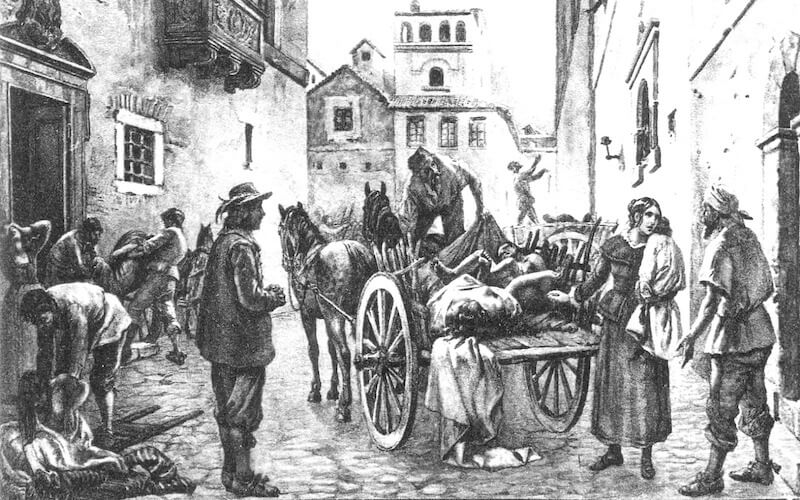

Manzoni’s description of the lazzaretto is as unforgettable as it is horrifying. It is there that Renzo finds Lucia. Both have recovered from the plague, thus making them immune. But all around them are people in agony, feverish, weeping, groaning, hallucinating. In one vast room, women who have survived but lost their infants are breastfeeding orphans. Processions of the sick stagger in to die. Carts stacked with naked corpses creak toward vast communal graves on the outskirts of the City.

Heroism. Just as dedicated doctors and nurses have given their lives in the coronavirus epidemic, healthcare workers died in Milan. But in those times, they were mostly monks who fed, cleaned and ministered to patients until they themselves dropped dead. That is the fate of Fra Cristofero, one of the central characters. In fact, Manzoni says, 60 priests in Milan died in the plague – about 90 percent of them.

And that was the plague that was. We don’t know how the coronavirus epidemic will end. But bird flu, SARS, and MERS have come and gone. And the Great Plague of Milan did too. As Renzo departs the lazzaretto, it begins to rain.

“This water carried off, washed away, so to speak, the contagion. If the lazzaretto did not restore to the living all the living it still contained, at least from that day it received no more into its vast abyss. At the end of a week, shops were opened, people returned to their houses, quarantine was hardly spoken of, and there remained of the pestilence but a few scattered traces.”

And Renzo and Lucia lived happily ever after.

Michael Cook is editor of BioEdge. This article was first published on MercatorNet.

Creative commons

https://www.bioedge.org/images/2008images/la-peste1.jpeg

coronavirus

- How long can you put off seeing the doctor because of lockdowns? - December 3, 2021

- House of Lords debates assisted suicide—again - October 28, 2021

- Spanish government tries to restrict conscientious objection - October 28, 2021