Did human genome editor He Jiankui deserve to be disgraced?

Not necessarily, say bioethicists

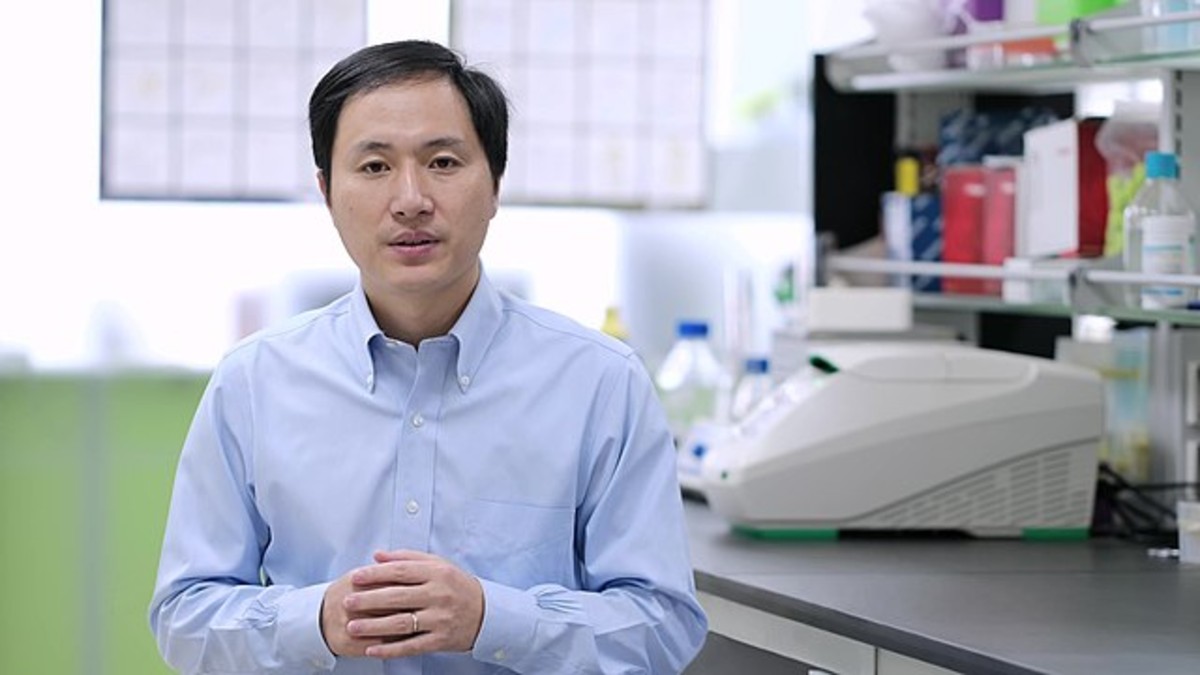

He Jiankui in his salad days

When Chinese researcher He Jiankui announced in late 2018 that he had helped to create the first genetically modified human babies, there was a firestorm of controversy. He was universally condemned. Shortly after the news broke, he disappeared and re-emerged in a courtroom where he was sentenced to jail for three years.

Breaking with the conventional wisdom about the ethics of He’s experiment, Chilean philosopher Marcos Alonso and Oxford University bioethicist Julian Savulescu question in the journal Bioethics whether the experiment was essentially wrong. There were significant procedural and safety issues, they acknowledge, but is it wrong to create a genetically modified human?

Their answer is a carefully qualified No.

They rely upon the famous non-identity problem set out by British philosopher Derek Parfit in 1984: “some actions also determine the existence, number or identity of future people. The peculiarity of these actions is that, strictly speaking, they cannot benefit or harm any individual, as they are the cause of their very existence.” In other words, were it not for He, the babies would never have been born at all. The genetic modification arguably has made their lives more healthy.

They conclude that using the non-identity problem to assess the ethical status of human genome editing is a useful tool:

We have many doubts about He Jiankui’s methods and motivations, which, as everything seems to indicate, were wrong and reprehensible. But it is paramount to understand why exactly something is wrong, even if we intuitively and firmly believe so. In this regard, it is crucial to distinguish between the aspects of his experiment that can be deemed as indisputably wrong, and the aspects that cannot be condemned—or less clearly so.

This distinction is crucially important to prevent a general negative backlash towards gene editing, a backlash that could paralyse or even set back gene-editing research and its implementation.

- How long can you put off seeing the doctor because of lockdowns? - December 3, 2021

- House of Lords debates assisted suicide—again - October 28, 2021

- Spanish government tries to restrict conscientious objection - October 28, 2021