Australia moves towards ‘assisted dying’

By the end of the year, New South Wales could be the only hold-out

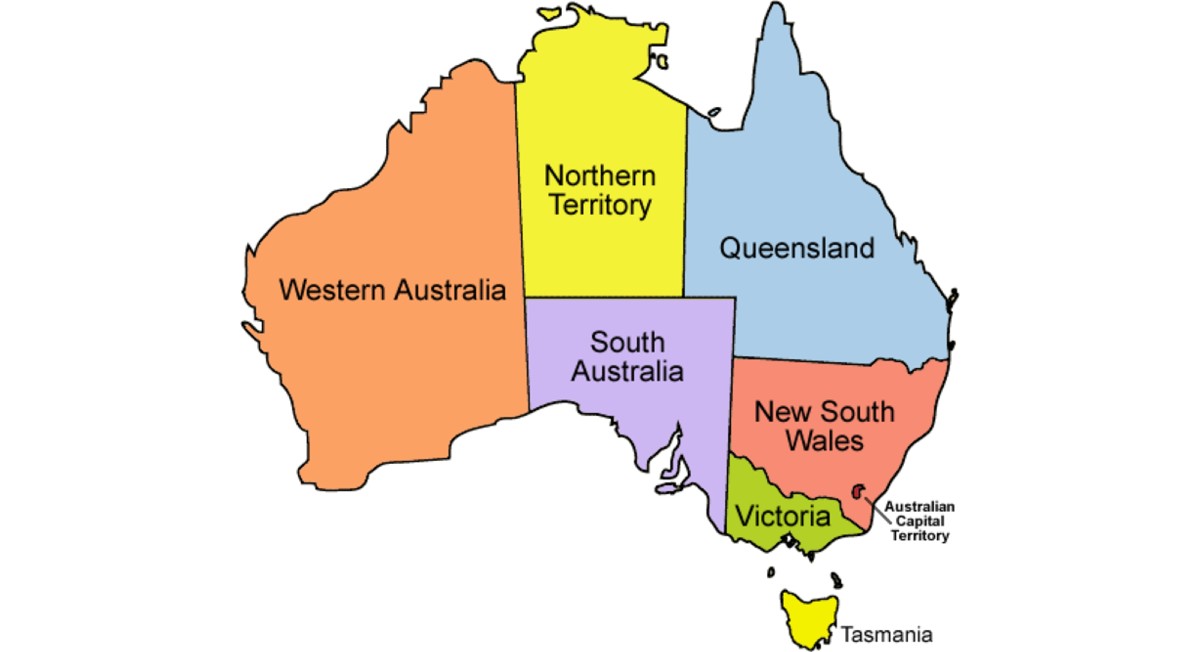

“Assisted dying” is on the way to make a clean sweep in Australia. Victoria’s legalised it in 2017, Western Australia in 2019, and Tasmania earlier this year. In South Australia a bill has passed both houses of the legislature and will probably pass in its final form later this year. Queensland’s premier is determined to pass legislation this year and will probably push it through the unicameral legislature.

Of Australia’s six states, then, five have could have “assisted dying” in place by the end of the year. MPs in the remaining state, New South Wales (whose capital is Sydney), will be under great pressure to pass an “assisted dying” law. Premier Gladys Berejiklian is a Liberal (conservative), but also a social progressive. While she may be reluctant to divide her own party, supporters of “assisted dying” argue that it is no longer electoral poison.

There are also two territories in the Commonwealth, but they were banned from passing euthanasia legislation in 1997 when the Federal government – which has the constitutional right to override territory legislation – quashed the Northern Territory’s right-to-die law.

Now, however, the chief minister of the Australian Capital Territory is keen to have “assisted dying”, as well.

Most of the legislation passed so far has been loosely modelled on Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act. But as the former chief minister of the ACT, Gary Humphries – a supporter of “assisted dying” — recently pointed out, the safeguards appear to be getting weaker.

… while there is a certain inevitability about making euthanasia legal in Australia, there are serious dangers if the wrong kind of euthanasia is enshrined in legislation.

As the headlong rush to legislate gathers pace, some of the safeguards built into the original Victorian legislation have been let slip. The Victorian act requires a patient to initiate a discussion about assisted dying, whereas more recent bills dispense with that requirement. The WA and Queensland provisions allow nurses to take the place of doctors in certain circumstances. And whereas earlier bills require that a patient have less than six months to live, the Queensland bill extends that period to 12 months.

This may not appear to be much of a slippery slope, but in fact it is. For some, the real objective is to be able to choose to die at a time, and in the circumstances, that they decide. The problem with this model is that, inevitably, people other than the patient sit around the decision-making table. Families play a role in such decisions, and their influence may not always be motivated by the best interests of the patient. The inconveniences of problematic ageing, family conflict and inheritance issues can all skew that discussion.

The looming victory of euthanasia lobbyists has prompted powerful interventions. One of the most commented on was an article by Paul Kelly, a former editor of The Australian, who is probably the country’s most respected journalist. He wrote: “Two ideas consume us. Extreme steps are deemed essential to save lives from the virus, while we authorise the state to liquidate lives in the name of humanity. On the one hand we strive to protect life through the health system, and on the other hand we move to terminate life through the same health system. Only a secular rationalisation decoupled from moral social principle could fail to be embarrassed by the juxtaposition. Yet we do not notice it.”

Michael Cook is editor of BioEdge

Creative commons

https://www.bioedge.org/images/2008images/australia-states_2.jpeg

assisted dying

australia